On the occasion of the 18th International Architecture Exhibition in Venice, from 14 May to 26 November Acp art capital partners - Palazzo Franchetti hosts the exhibition Kengo Kuma - onomatopoeia architecture , curated by Chizuko Kawarada (partner of the Kengo Kuma&Associates studio), and Roberta Perazzini Calarota (president of Acp art capital partners).

What is Kengo Kuma's onomatopoeic architecture?

On display, for the first time, the onomatopoeic architecture of Kengo Kuma, i.e. the ability of the Japanese master to tell his projects to collaborators and clients through onomatopoeic words, in a simple, almost childish way, free from theoretical superstructures.

"If I had to explain my concepts in words, it would be very difficult for me to understand", says Kuma, "then I express them through sounds, which evoke materialities".

Thus the architect has identified thirteen onomatopoeic Japanese words, around which the exhibition revolves, which summarize the key points of his design practice, from 'para para', which means 'full and empty', to 'zure zure' which means 'offset, flexibility'.

"Every time I go to Venice and feel close to water as 'material', I think of the dialogue between the human and the material", continues Kuma.

What will we see at the exhibition on onomatopoeic architecture by Kengo Kuma in Venice?

"In this exhibition at Palazzo Franchetti I would like to show how I create a dialogue with materials. In this dialogue I almost never use logically influenced language. And when I use it, it's impossible to make myself understood. That's why I always use onomatopoeia. Matter and body speak to each other and resonatewhen they use this primitive language".

The exhibition is explained to us by Marco Imperadori, a professor at the Milan Polytechnic and a longtime friend of Kengo Kuma. Imperadori gave his scientific contribution to the exhibition and wrote the catalogue: Kengo Kuma - onomatopoeia architecture, Dario Cimorelli Editore, 144 pp, 30 euros.

Can you explain the title of the exhibition Onomatopoeia architecture?

Marco Imperadori: "This exhibition is truly original because Kengo Kuma for the first time talks about his singular method of expressing his ideas through sounds, associating architectural concepts with onomatopoeic words.

An exhibition not to be missed also because the architect in Venice reveals more intimate and personal nuances, such as the fact of being attracted by soft materials because they remind him of his mother.

The title of the exhibition Onomatopoeia architecture quotes the book Onomatopoeia written by Kuma in 2015, in which the architect says: "If I had to explain my idea of architecture in words, it would be very difficult to make myself understood; then I express myself through sounds that evoke materialities, with onomatopoeias that are closer to physical sensations".

Kengo Kuma with his onomatopoeic terms wants to create a bridge between man and nature, it is a very poetic and very Japanese approach.

For this exhibition, Kuma identifies thirteen onomatopoeic Japanese words, whose repeated sound, a bit funny and a bit manga-like, translates some key terms of his design practice.

The architect uses these sound-words to communicate and transmit the projects to his collaborators and clients, to evoke sensations, saying, for example: "I would like this project to be more 'para para', more played on solids and voids" .

It is a very original concept in architecture: instead of using complex theoretical-philosophical lucubrations, Kuma explains empathy with materials purely through sounds. And he adds: "We have to make architecture on a human and nature scale, to resonate with the materials through a voice, which is precisely the one expressed by these onomatopoeic words".

What link is established between the exhibition, the architecture of Kengo Kuma and the city of Venice?

Marco Imperadori: "This exhibition is also a tribute to Venice, "the most onomatopoeic city there can be", as Kuma himself points out, an invisible city, built on water, which is reflected, it is mirrored, which also recalls Japanese aesthetics, imperfection, what is ruined due to constant contact with water.

So the exhibition also speaks of the ephemeral, which is a characteristic that unites the oriental spirit and the lagoon city".

How is the exhibition organised? What will the public see?

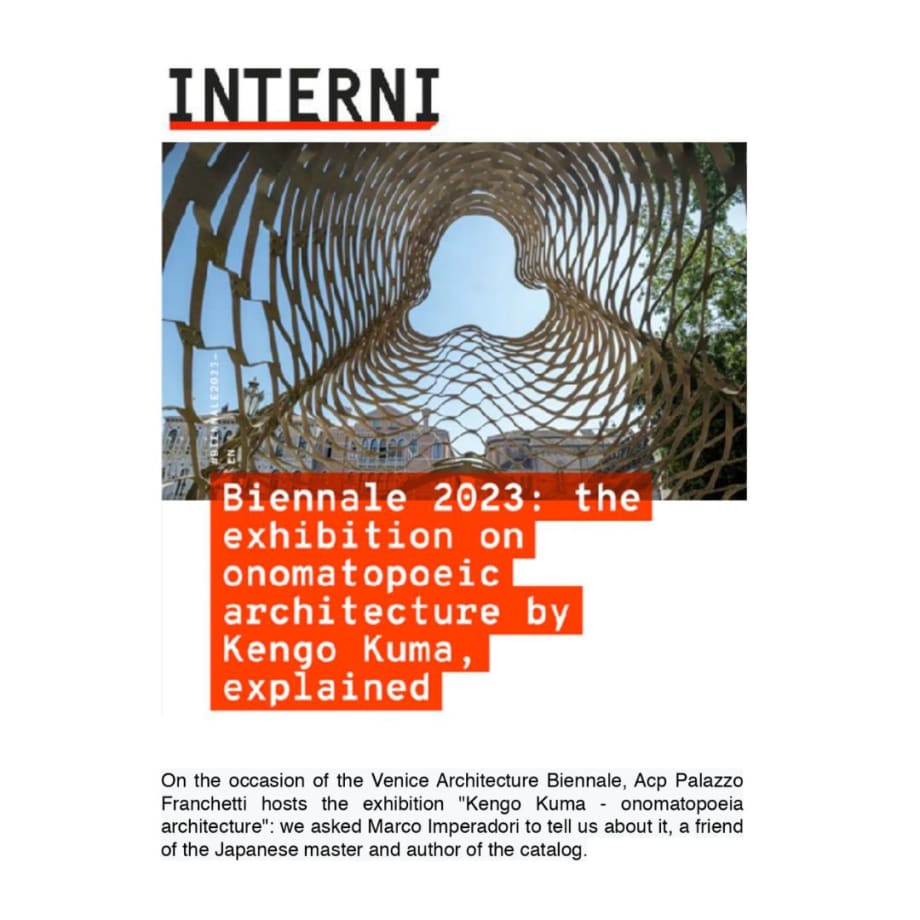

Marco Imperadori: "The exhibition is hosted in Palazzo Franchetti, on CanalGrande. In the large outdoor garden there is Laguna, one of the two site-specific works by Kengo Kuma created by the craftsman D3Wood, based in Lecco: Laguna is an aluminum sheet five meters high, milled, stretched and then sandblasted with sand from the Piave, which, like a big wave, or like a maxi net, emerges from the garden and 'captures' the visitor.

Entering the sumptuous palace, you come across Albero della boat, the second site-specific work, a sculpture 'tsun tsun' Kuma would say using one of his onomatopoeias, a sort of waves, or a planking of a boat exploded by the force of the sea, in chestnut blades, a wood resistant to humidity, chosen by Kuma because it was used in the past for the foundations of Venice.

Then we enter the heart of the exhibition, an architectural promenade punctuated by the rooms divided according to the thirteen onomatopoeias chosen by Kuma, where each onomatopoeia is explained through photographs and models of the most recent by the architect.

Visitors will have an audio-guide, and in each room there is a billboard in which the architect translated the onomatopoeias by hand-drawing the kanji, i.e. the ideograms Japanese, and the corresponding graphic concept. An example? 'Para para', which in Italian means "full and empty", is represented by dots".

What are the thirteen onomatopoeias chosen by Kengo Kuma, told in the exhibition?

Marco Imperadori: "The first, 'para para', evokes fullness and emptiness, and is represented by porous architectures, such as the designed by Kengo Kuma for the Tokyo 2020 Olympics.

The second onomatopoeia is 'sara sara' and means fluid, soft: an extraordinary example of this fluid softness, made up of light, shadows and air, is the Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto. The third is 'guru guru', and means 'fluid/tornado-vortex', explained by Kengo Kuma with The Darling Exchange building in Sydney, a small 'urban tornado'.

The fourth onomatopoeia is 'suke suke', i.e. 'horizontal, flat, evident in the Glass/Wood House in New Canaan, where the horizontal plane detaches itself from the ground, in a surprising and original way, thanks to thin metal columns and wooden beams, like a nest supported by the trunks of the surrounding trees.

Then there is 'giza giza', which means 'hard, fold' and refers to the sensation of hardness and rigidity of the constructive particles; 'zara zara', the rough texture; 'tsun tsun', 'pressure, explosion', represented by thin Japanese cypress rods that cross, like the twigs of a nest, to give life to the Sunny Hills store in Tokyo.

Then there is 'pata pata', 'light, fold'; 'pear pear', 'piano, finesse', that is light, sweetness, subtlety; 'fuwa fuwa', which stands for 'elasticity, membrane', and refers to softness. Finally 'moja moja', that is 'wave, line'; 'funya funya', i.e. 'relaxed and soft', and 'zure zure', 'offset and flexibility'".

Which of the projects on display best summarizes Kengo Kuma's approach?

Marco Imperadori: "I would choose Kodama, the work by Kengo Kuma for Arte Sella, at Villa Strobele in Trentino, which I followed as scientific director of the architecture and design part of the park. Kodama means 'spirit of the forest', it is a small tea room in the middle of the woods which expresses the onomatopoeia 'pata pata', that is 'light and folds', a nest where the light filters clear among the wood particles.

A work that on the one hand summarizes Kuma's concept of triple porosity,characterized by the triple void made up of exterior, interior and porosity between the structural tesserae, and on the other expresses the theory of fragmentation, because it is made up of many small pieces of wood joined together.

Kengo Kuma has written many books on the theory of parcelization: according to the architect, we humans have a small body and we cannot compare ourselves to a large box made of reinforced concrete, modern materials for him are often beyond the human scale.

The master instead uses wood and materials that he can fragment, to bring architecture closer to man, to create an intimate dialogue between the building and those who live in it. This is why its facades and structures are always parceled out, made up of many elements, it is like looking at a large tree with many leaves, a division that brings you closer to the tree, even if it is forty meters high.

Another fundamental work is the aforementioned Tokyo stadium for the 2020 Olympics. Zaha Hadid initially won the competition for the construction of the stadium, but then the project was blocked because it was too expensive and out of context. Kengo Kuma's project was more convincing: a 'para para', solid-empty building, formed by discs of various levels alternating solids and voids, like a large circular pagoda".

The way Kengo Kuma approaches materials is a key point of his originality.

Marco Imperadori: "Kengo Kuma says: "Through the material we can learn to know the place and get closer to its specificity. By becoming friends with the materials, I was able to learn the most important things".

When Kuma visits a place it is as if he has to feel all the sensations of the place. So if there are historic buildings, he sees, touches, and from there his creative process begins, driven by the desire to empathize with the territory and with local materials through this translator which are the onomatopoeias ".

Kenzo Tange, Japanese master of architecture, made extensive use of concrete in the 1960s. Why does Kuma deviate, preferring ancient and natural materials such as wood, bamboo, raw earth and washi paper?

Marco Imperadori: "Kengo Tange was the 'samurai shogun' of Japanese architects. We are in the sixties and seventies, it is the Japanese economic boom.

Designers such as Tange, but also Metabolists and authors such as Arata Isozakiand Kisho Kurokawa aim for modernity, building impressive muscular buildings in concrete.

Kuma does not follow this line, but wants to react, because he remembers the Tokyo he knew as a child, a small and widespread Tokyo, made up of wooden houses, that smallness typical of Asia swept away by the big economic bubble.

He decides to do a research doctorate with Hiroshi Hara, his true master, and goes to Africa to study villages; observing the fragmentation of spaces and African houses, Kuma theorizes the concept of fragmentation, which will accompany him throughout his career ".

When did you meet Kengo Kuma?

Marco Imperadori: "Twenty years ago, and we have always remained in contact, he was an honorary graduate of the Milan Polytechnic, I was the one who pleaded the cause, we are proud of it.

He is a human person, not a star at all, although he shines in his own light. He is very friendly, available, when we meet we go out to dinner, even with his wife Satoko Shinohara, also a famous designer, and his son Taichi who works in his father's studio.

Kuma is a real person, like his architecture. Despite his success, he does not follow clichés, his architecture is never repetitive, there is always continuous variation, and this is typical of great masters.

He also devotes a lot of time to training, teaches at the University of Tokyo, wants to transmit".

When was Kengo Kuma's vocation born?

Marco Imperadori: " As a child he wanted to be a veterinarian. Then, one day, as a child, while swimming on his back in the pool of the Yoyogi stadium designed by Kenzo Tange for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, looking at the imposing, almost overwhelming, reinforced concrete ceiling, he decides he wants to do something different, lighter, smaller, wooden, something more human.

It is interesting to note how Kuma, designing the stadium for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, has come full circle, completely departing from the muscular, and not very empathic, stadium of Kengo Tange from the 1960s".